The Art of Writing Great Music

Music is a creative process, sometimes involving what seems like a purely emotional expression. But, all creative expression has its rules and boundaries.

When drawing a realistic scene, an artist must use a vanishing point. When carving a statue, a sculptor must chip away only so much and in the right direction. A painter must combine certain primary colors to get secondary colors, etc. You get the idea.

In music, there are certain rules that must be followed to achieve certain outcomes. Three notes make a chord, but they can’t be just any three notes; they must be arranged in a certain order. And, certain orders of notes or certain intervals impart different responses in people.

The best first thing that you can do is to get a firm foundation of music theory. It doesn’t need to be extensive, but it should include more than a rudimentary understanding of notes, keys, time signatures and chords. Review my article called How to Use Music Theory to Write Good Music to get a better understanding of what you need to know. This article will deal with how to bend some of those rules.

No person or group of people invented a lot of what we call music theory. Time signatures, key signatures, staffs and other things existed in a number of forms before the ones we use now were agreed on about 1,000 years ago. The intervals we use are a natural occurrence found in the overtone series. (See the end of my article entitled Inside a Great Arrangement – Part Three for more details). Still, there are certain things that sound better to one’s ear than others, and certain intervals, melody forms and chord progressions that evoke certain emotional and intellectual responses from people.

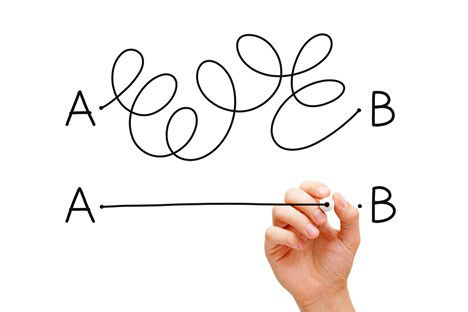

Following all those guidelines can stifle a composer’s creativity if you wrote everything strictly by the rules. So, how do you use these rules to write good songs and other music? The first thing is obvious; you need to know the rules.

In reference to the artist mentioned above – If the artist doing the drawing wanted to make some or all of his drawing convey an uneasy feeling, he could use two or more vanishing points, or none at all. The sense of realism would be gone and there would be more sense of surrealism.

The artist doing the painting could employ neutral tones between the color transitions in her painting to counter the natural way that colors interplay with one another.

Each of them, then, would need to know the rules and know how to competently use the rules before they could use any alternative rules.

Many times, as I’m writing, whether it’s a pop song, concert band piece or choral piece, I can do large chunks of it in an “inspired” mode. The rules are always floating around in the back of my head, and I choose this or that as I go. But, then, there’s a situation in which I need to get from one section to another smoothly, even cleverly, but nothing comes to mind.

So, I do a formal analysis of what I’ve done so far and see which rules, “proper” or alternative, can help me make the connection. (If you have the opportunity to analyze some of Bach’s works, do it. You can analyze ANYONE’S works after that.) Once I see what I’ve BEEN doing, I can expand on that.

There are always (at least there should be) melodic, rhythmic and/or chordal motifs for you to develop. Can the melody be shifted or inverted somehow? If the melody centers around a few notes, it can be widened with larger skips. Or vice versa.

EXAMPLES

- Use Simple, but Effective Melodic Motifs – You remember the main theme from the movie “Jaws”? It was based on a set of only two notes and conveyed a sense of foreboding. If you listen to movie and TV music, and classical music before and after the “Jaws” movie, you will find the same two-note theme used to conjure a sense of fear. It’s part of human psychoacoustics.

- “Morning Star Serenade” for Concert Band is a composition by Salt Cellar that has a fairly simple main melody, although not as simple as the “Jaws” theme. Throughout the piece, the melody appears often, but with different chords underneath. That way, it tends to move and it doesn’t get stale.

- Don’t Play It Safe – In Salieri’s Piano Concerto in C Major, he follows all the “proper” rules for most of the piece. He depends on the emphasis of some notes and chords for a little “bite’ to the music, something that all music needs. It presents itself as a nice, feel-good piece. However, he plays it safe and the result is a piece that doesn’t really go anywhere.

One of Salt Cellar’s oddest pieces for Concert band is called “The Cantummit Waltz”. It’s in an easy-going 3/4 time, but the biggest “rule” that is breaks is that the theme is in seven-measure phrases. If people were to try to dance properly to it, they would find that they would be missing a step. There are also a couple of odd chord changes. For the sake of resolution, the melody gains an extra measure in the end and it sounds more finished and complete to the listener. - Know Which Rules to Break and When – In Mozart’s Ein Klein Nachtmusik, he follows ALL the rules for the first minute or so. Remember, this music was written for a relaxing evening, so it had to start out “comfortably”. In a while, he starts bending the rules. Actually, he started using some rules that aren’t used so much. They add the “bite” in his music. Then, after repeating the whole first section, he goes off on a little tangent to add some more interest before wrapping it all up. He used the “proper” rules for most of it and achieved the “bite” with a few well-chosen “alternate” rules.

Most arrangements of any sort generally take an established piece and create a different voicing for it, sometimes with some alternate chords or added embellishments. Salt Cellar has done a unique arrangement of “Amazing Grace” entitled “How Sweet the Sound” in which the melody is recognizable, but not the same. The time signature is 4/4 instead of the traditional 3/4 and the smoothness has been replaced by an energetic interpretation.

- Keep It Simple and Consistent – For a relatively more modern comparison, consider Credence Clearwater Revival’s Bad Moon Rising. It has three chords, all of which are the basic three in any major key, the 1, 4, and 5. The only “proper” rule that they don’t follow is a full cadence, going from the 5 chord to the 1 (tonic) chord. They use what’s called a plagal cadence., which is a 5, 4, 1 progression. “Bad Moon Rising” is in the key of D., with D being 1, G being 4 and A being 5. Their chord progression is | D | A / G | D | D | . This is repeated four times. Then, it changes up a bit with | G | G | D | D | A | G | D | D |. The D chord is never preceded by the A chord, yet it still sounds solid. It’s not that a plagal cadence is bad or never used, it’s just that in most songs that move well, a full cadence is generally used to end the song or a section.

“Jewels and Treasures”, a piece for String Orchestra by Salt Cellar, has a relatively simple melody while the accompaniment changes underneath it. The chord progression, unlike “Bad Moon Rising” is a little more involved, and it end with a full cadence.

- Use The Rules, But In A Different Way – Lastly, The Beatles did quite a few things with the alternative rules. In “All You Need is Love” the introduction starts with a snippet of the French national anthem. Then, it mixes up the time signature, first in four then in three, then in four, then in three, etc. The Chorus, however, is in an easy-going four, a resolution to the bit of uneasiness created by the mixed-up time signatures. The chords are basically in the range of “proper” relationships, too.

Another piece for String orchestra by Salt Cellar is “Golden Morning” in which the simple, folk-like melody is accompanied by lush chords underneath that, were they to stand on their own, would be a simple chord progression. However, the simple melody and simple chord progression are blended in such a way that is produces a number of quickly passing dissonances.

Finally, you can write great music only if you know music. When I went to college to study music, I knew at least a dozen chords on the guitar and could bang away on the piano with the best of them I didn’t think that I needed to know any more than that. When I finally resigned myself to study the music they wanted me to study, I discovered not only what I had really been doing, but a lot of other wonderful and valuable things from classical music that I could use in pop and rock. A wise person once said, “The more I know, the more I know what I don’t know”.

Salt Cellar Creations understands the art and skill of writing great music, especially music that will fit student music ensembles. We have a growing library of original works and arrangements. Find out more about all the music that Salt Cellar Creations has to offer HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!