Using Key Changes to Add Zing to Your Music

It’s a sad commentary on a lot of contemporary music, both secular and sacred, that the music is in one key for the whole song or serious composition. Even popular music of several decades ago had some interesting key changes in some of them. The writers were careful not to use a key change in every song. That can also become old and tiresome.

When composing or arranging music, The Key Change is a powerful technique that you can use to inject freshness and vitality into that music. Whether you're a budding songwriter or an experienced musician, mastering the art of key changes can elevate your music to new heights, captivating listeners and leaving a lasting impression. Let's examine different ways to effectively employ key changes to make your music more engaging and memorable.

Understanding Key Changes

At its core, a key change involves shifting the tonal center of a piece of music from one key to another. This transition introduces a sense of movement and progression, enriching the listening experience. Key changes can occur suddenly or gradually, depending on the desired effect and musical context.

Adding Variety and Momentum

One of the primary benefits of incorporating key changes is the injection of variety and momentum into a composition. By changing key, usually by going up a step or two, you can rejuvenate the melodies in the piece and prevent listener fatigue. Consider strategically placing key changes at pivotal moments within your song to maintain interest and captivate your audience.

Building Emotional Depth

Key changes have the power to evoke a range of emotions, enhancing the depth and complexity of your music. A well-executed modulation can convey feelings of excitement, anticipation, or resolution, allowing you to connect with your audience on a deeper level. Experiment with different keys and modulation techniques to evoke the desired emotional response in your listeners.

Enhancing Musical Structure

Key changes can also serve as structural devices, guiding listeners through the journey of your composition. By introducing key changes at key structural points, such as before a chorus in a pop tune or between sections in a sonata or rondo in more serious music, you can create a sense of progression and development. This not only adds cohesion to your music but also keeps listeners engaged from start to finish.

There are some instances where a pair of singers, most often a male and female, are sharing a song. One key is great for a melody and its harmony being sung by each of the singers. However, when the one singing harmony is then supposed to sing the melody, the range is just not right, so the key must be changed to accommodate the singer’s range.

There are other times, such as is a concert band or string orchestra piece, when the fingering for one type of instrument is great for the music being played at the moment, the melody for example. But, if another instrument were to play that melody, the fingering would be cumbersome at best. Then, the key must be changed to accommodate the instrument playing the melody.

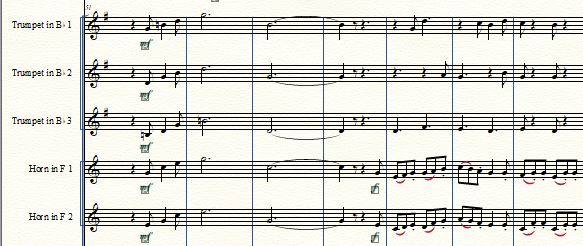

Here is one example from Salt cellar’s library of original music for Concert Band called Carry Me Back to Old Killarney. To hear the whole piece, click HERE. Below, you’ll see two lines of music. In the first, the trumpets have the melody in the key of F major. The fingering involves only the first two valves and is quite easy, although the player has to pay a bit of attention to the embouchure. In the second, the French horns are in the key of Bb major. If they tried to play the melody in that key, it would be very awkward it it were playable at all. So, the key was changed one whole step higher, which not only gave the whole piece a bit of energy, but also gave the French horn players a melody that is equally as easy as the trumpet part is. And, the other instruments still have music that is very playable, if not positively easy.

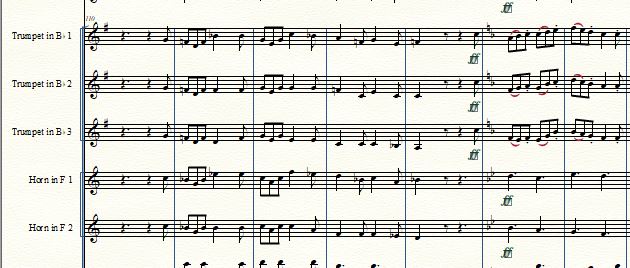

Later in the piece, the key returns to its original position. This was accomplished by using a few fleeting alternate key centers. The example below shows the end of that set of alternate key centers and how it returns the piece to its original key.

Practical Tips for Implementing Key Changes

Now that we've explored the benefits of key changes, let's discuss some practical tips for incorporating them into your music:

1. Choose the Right Moment:

Consider the overall mood and narrative of your song when deciding where to introduce a key change. Aim for moments that naturally lend themselves to heightened tension or emotional impact.

In more traditional churches, a good organist would play an introduction to a hymn, then he or she would play each verse with music that fit well with that particular verse. If there were three verses, after the second verse the organist would play what might be called a bridge, but it was so much more. It may be two measures or sixteen, but this was the buildup to the last verse. This improvisation would wander the melody and harmonies through a circle of fifths or fourths or some other creative path and end very firmly in the new key, which was always one or two half steps higher This would be part of the organist’s praise offering since singing was out of the question, due to the tremendous concentration it takes to play the organ properly.

2. Experiment with Different Keys:

Don't be afraid to explore a variety of keys when modulating. Each key change brings its own unique color and character to the music, so experiment until you find the perfect fit. Sometimes the transition from one key to another may take a route through a minor chord or two, or through a couple of chords that wouldn’t be considered “normal” in other situations.

However, you need to be careful and thoughtful. Remember that not all keys are good for all instruments or voices. Guitars, violins and other string instruments generally prefer key signatures with sharps, but no more than three or four. Wind instruments generally prefer key signatures with flats, but also with no more than three or four. They can maneuver in key signatures with sharps if there are about three or less.

And, vocalists need to work well within their normal range. An occasional high or low note is tolerable, but if the tessitura is too high or low, it can strain their voices.

3. Transitions:

Pay attention to the transition between keys. Sometimes, you need a seamless and natural flow. For that, you need to utilize common chord progressions or pivot chords to facilitate smooth modulations without jarring the listener. Other times, you want to through a splash of cold water in the listener’s face and use a sudden change of key center.

Examples:

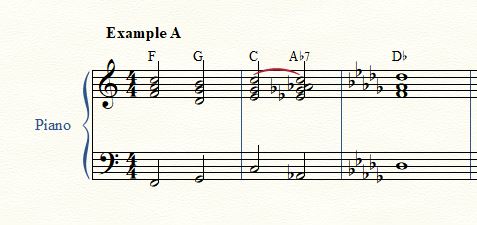

PLEASE NOTE that all examples start with a full cadence – 4, 5, 1. Not all cadences are like that, but this will give you a good starting place. Also, note that all the key change examples use a full cadence, except one. It’s very difficult to change key using a Plagal or other false cadence. Most of the names given to the different types of cadences are not found in any music theory books; they are my own invention. The only ones that are actual musical terms are the Modal Insertion Wagner Cadence and Parallel Key Change.

- Half Step Simple – This one uses a true suspension in which the last note of the melody was on the tonic. It is held while the new dominant is “installed” underneath it. Example A shows how to go from the key of C to D flat. The melody ends on the C. An A flat7 is created and the song easily slips into D flat. This one is more suitable for keyboards and advanced instrumental ensembles, whether wind or strings.

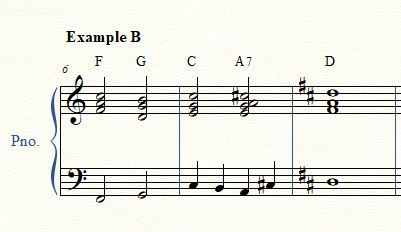

- Whole Step Simple – A very similar one that works not only for wind or string ensembles, but also for guitarists would look like this. Example B shows that to get from the key of C, you can add an A major or an A7 to go to the key of D. You notice that the bass line helps drive the key change. Even middle school instrumentalists can use this one, if you stay within the easier keys.

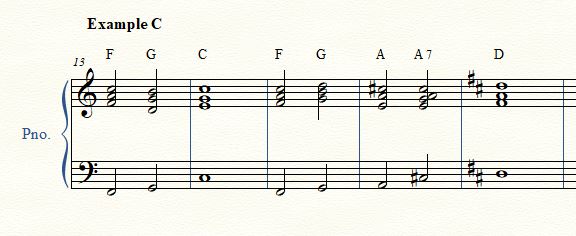

- “Pushed Dominant” – Example C demonstrates this technique. The ear is tricked into thinking that the A and A7 chords belong there. It borrows from the concept of modes. The practice is used in movie and Broadway scores to add excitement to a scene, etc.

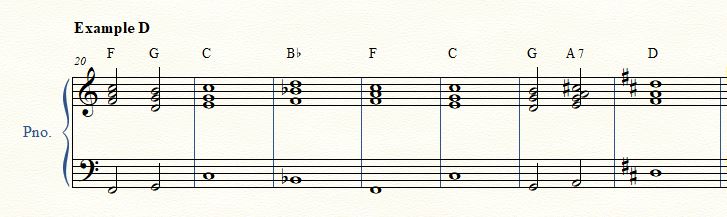

- Modal Insertion – Example D employs a true modal insertion, that is, a chord that isn’t in the normal available set of chords for a key, and which was part of one of early church modes. It goes directly from a C to a B flat. Then, it goes down a fourth to F, then to C, but it doesn’t sound like it’s landed on tonic; it just sounds like another chord on the “journey”. From the C it continues to G. Now we have to firmly introduce the new key, in this case, D, so we use the G as the subdominant and add an A / A7 and land on D.

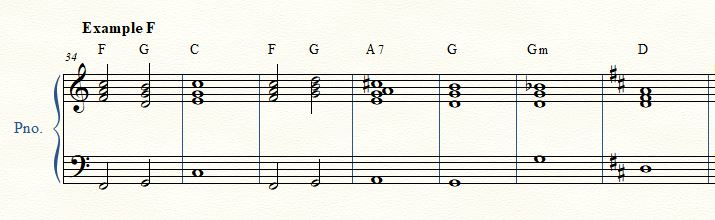

- Wagner Cadence – So far, the new key has been preceded by its dominant chord. This is the most effective way of establishing a new key. Occasionally, a new key may be established by using a subdominant followed by a minor subdominant. Example F shows one possibility.

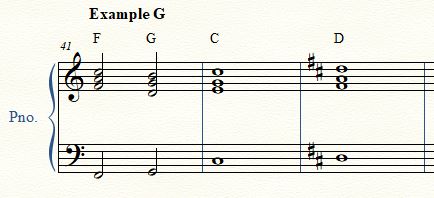

- Big Splash – This type of key change is sudden and abrupt. There is no preparation for it because it’s meant to take the listener by surprise. Example G demonstrates this key change. It works best if the music itself has some strong chord changes at the beginning of a verse or section. If the first few measures in the key of C were | C / F | C / G | Am / G | C / G | , then, when the music changed to the key of D, the progression would more firmly establish the new key. If the chord progression were somewhat sedate, the new key might be difficult for the listener to accept. This is true for most key changes.

- Parallel Key Change – Sometimes, you can simply change from a songs major key to its parallel minor key or vice versa. A major to A minor. There aren’t a lot of opportunities for this one, but its dynamic when it has that opportunity. Sometimes, a major dominant chord is necessary to switch back to the original key so that the listener’s ear doesn’t become confused. There’s no example needed for this one.

Conclusion Incorporating key changes into your music is a powerful way to add depth, variety, emotional resonance, and appropriate accommodation to your songs and compositions. By understanding the fundamentals of the key changing process and experimenting with different techniques, you can unlock new creative possibilities and take your music to the next level. Your music will come alive with newfound energy and excitement when you embrace the art of key changes.

One final word. Key changes must be used carefully. My church organist story emphasizes that. The organist only changed key for the last, usually more noble sounding, hymn. If it had been used for everything, it would have lost its distinctiveness. So go ahead, use them, but make save them for special occasions.

Salt Cellar Creations has the knowledge and skill to write and arrange music, including the judicial and beneficial use of key changes, bringing out all the beauty and power that a musical piece possess. We have a growing library of original works and arrangements with which to demonstrate this. Find out more about what Salt Cellar Creations has to offer HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!