How Dissonant Chords Provide Power and Beauty in Choral Music

Music, as an art form, has the remarkable ability to evoke emotions, connect souls, and communicate across cultural and linguistic boundaries. Choral music, in particular, carries a unique potency, with its rich tapestry of voices intertwining to create sweet or somber melodies that resonate deeply within listeners. Among the various techniques employed in choral compositions, dissonant chords stand out as a mysterious force that adds both complexity and allure to the musical experience. When used effectively in choral compositions, dissonance can evoke strong passions, create tension, and ultimately bring about a satisfying resolution. Dissonance has been used throughout the history of choral music to add depth, drama, and complexity. From the chromaticism of the Renaissance to the lush harmonies of the Romantic period, composers have long employed dissonance to create unique soundscapes.

In this article, we will explore how to apply musical dissonance to choral compositions in a way that enhances the musical experience.

Definition and Examples of Dissonance

Many things are open for interpretation. How loud is too loud? How quiet is too quiet? How many notes are too many? Dissonance is also one of them. The technical definition is – Intervals or chords that sound rough, tense, and clashing. They often resolve to consonant intervals or chords.

The foundation of traditional harmony is built upon consonant chords, which are stable and harmonious to the ear. Consonance provides a sense of resolution, creating a feeling of closure and contentment. Consonant intervals are generally agreed on to be the octave, perfect fifth, perfect fourth, major third and minor third. Beyond that, there is quite a bit of discussion.

Dissonance, on the other hand, is characterized by tension and instability. In choral music, dissonant chords challenge conventional expectations, forcing listeners to confront the unfamiliar and expand their auditory horizons.

The concept of dissonance has changed over the centuries. When polyphony was first used in the 9th to the 16th centuries, the only consonant intervals “allowed” were the octave, perfect fourth and perfect fifth. Anything closer was considered dissonant. This form of music was also known as organum and was the only form of vocal polyphony. It is two melodic lines moving simultaneously, sometimes creating an imaginary chord. Sometimes a second, or organal, voice doubled the principal voice at an interval of a fourth or a fifth below. It was for both vocal and instrumental music. This method increased the likelihood of creating a true chord.

As decades passed and composers longed for more colorful chords, major thirds passed from their designation of dissonant to consonant. As time progressed, more and more intervals became considered consonant. However, certain intervals such as a minor second, diminished fifth, and major seventh are still considered dissonant. Even modern ears cannot consider them consonant.

Incorporating dissonance into choral compositions requires a delicate balance, as too much tension can overwhelm the listener, while too little can lead to predictability. Composers and arrangers navigate this fine line with precision, strategically placing dissonant chords to punctuate key moments in the narrative. This contrast between dissonance and consonance mirrors the complexities of human experiences, where moments of tension and resolution shape our personal growth and understanding of the world around us.

Emotional Resonance

One of the most captivating aspects of choral music lies in its ability to convey emotions that words alone often struggle to express. Dissonant chords play a pivotal role in this emotional landscape, adding depth and nuance to the musical tapestry. By invoking tension and unease, dissonance can mirror feelings of conflict, longing, and uncertainty. These emotional states resonate profoundly with the human condition, reflecting the complexities of relationships, aspirations, and inner struggles.

Consider a choral piece that explores themes of sorrow and mourning. Dissonant chords can effectively capture the raw, heart-wrenching feelings associated with loss. As the voices of the choir converge and diverge, creating dissonant clashes that gradually resolve, listeners are taken on an emotional journey that mirrors the process of coming to terms with grief. In this context, dissonance becomes a vehicle for empathy, inviting listeners to connect with the universal emotions that unite humanity.

Aesthetic Complexity

The allure of dissonant chords in choral music lies in their ability to elevate the composition's aesthetic complexity. Much like a painter uses contrasting colors to create depth and dimension on a canvas, composers use dissonance to add layers of sonic complexity. This complexity engages the listener's cognitive faculties, inviting them to unravel the intricacies of the musical arrangement.

Imagine a choral piece inspired by the interplay of light and shadow in a forest. Dissonant chords can represent the dense underbrush and hidden mysteries of the woods, contrasting with moments of consonance that evoke the serene beauty of sunlight filtering through the trees. By blending dissonance and consonance, the composer crafts a musical landscape that mirrors the visual and emotional experiences of wandering through a forest. This multi-dimensional approach draws listeners into a world where sound becomes a conduit for imagination and contemplation.

Divine Dissonance

For Christians, the concept of dissonance in choral music can also be understood in a spiritual context. The Christian journey is marked by moments of struggle and doubt, as well as moments of profound victory. Dissonant chords, with their tension and release, can be seen as a reflection of this journey—an artistic representation of the challenges and triumphs that define the human relationship with God.

In Biblical narratives, the stories of struggle, doubt, and redemption are central to the Christian faith. The use of dissonance in choral music can amplify these themes, creating a musical dialogue that resonates with the core tenets of Christianity. As dissonant chords resolve into consonance, they symbolize the path from turmoil to peace, from doubt to faith, from death to life in Jesus, echoing the transformative journey that lies at the heart of the Christian life.

Techniques for Applying Dissonance

In choral music, dissonance can manifest in various forms, including harmonic dissonance (when chords clash) and melodic dissonance (when notes within a melody create tension). The key to using dissonance effectively is knowing how and when to resolve it. Here are some ways to use dissonance in a choral composition or arrangement:

- Suspensions: A common technique in choral music, suspensions occur when a note from one chord is held over into the next, creating a temporary dissonance that resolves as the note moves to a consonant pitch. This can be used to create a sense of expectation and release.

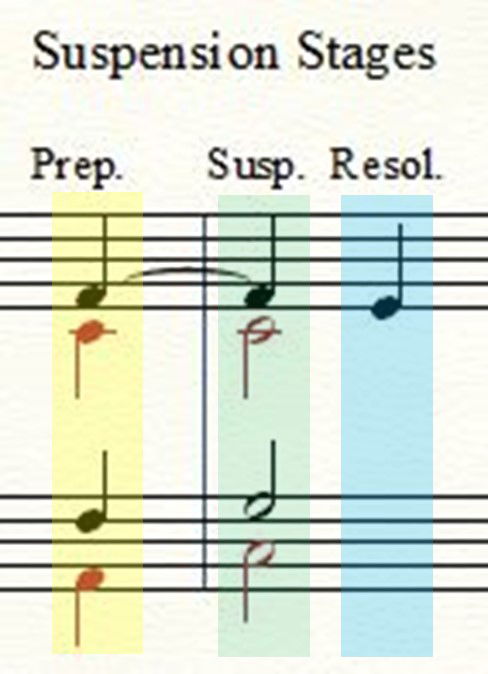

A musical suspension is comprised of three stages. They are the Preparation, Suspension and Resolution. (See example below.) In the preparation, the note played is part of the normal harmony and can occur in any part. In the suspension, the prepared note is held as the other parts change and a new chord is formed. This creates a dissonance between the held note and the new chord. The resolution occurs when the suspended note falls by either a half or whole step to a note in the new chord. In traditional harmony, the resolution always occurs on a weaker beat than the suspension. If the music was in 4/4 time the suspension would typically occur on the first beat of the measure with the resolution on beat two or three. Below is a sample of the three parts of a suspension.

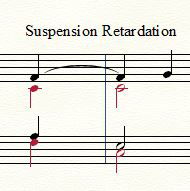

Most resolutions are resolved with the suspended note moving down a step. However, you will find that some suspensions resolve upwards – this is called a “retardation”. It may have been named that because it occurred when the music was slowing, if only for a few measures.

A suspension, in modern usage, can also use the introduction of the movement of notes to imitate a true suspension. In some modern works, composers may leave suspensions unresolved to create a persistent dissonant sound. Here are some example of suspensions, whether they are true suspensions or “inserted” suspensions:

- The most common is the Suspend-4. In it, the fourth note in the scale is held over from the previous measure, or converted from the third note to the fourth. This creates dissonance between the fourth and fifth of the scale. Most of the time, it resolves down to the third, although there are times when the melody or harmony calls for it to resolve upward. The upward resolution requires a bit more planning to make it sound good.

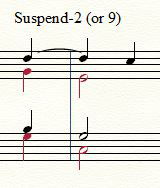

- The next common one is a Suspend-2 (or 9). In it, the second note is held or inserted and usually resolved down to the one (tonic) place. It creates dissonance between the second and third of the scale. Sometimes it is voiced so that it also creates dissonance between the second and the tonic in another part. It is also one that may be resolved upward as a retardation.

- Another one is a Suspended-6. Here, the sixth note in the scale is held or inserted and resolved to the fifth of the scale. It is never resolved upward since it would create a major seventh chord, which contains even more dissonance than the suspended sixth.

- Appoggiaturas and Acciaccaturas: These non-chord tones appear as what are commonly called grace notes. They add dissonance by introducing notes that don't belong to the underlying chord. Appoggiaturas are typically longer, actually stealing some of the duration of the “host” note. Even though they are notated as grace notes, they can be as long as a half note I duration, especially in works of more modern composers. Acciaccaturas, on the other hand, are shorter, stealing no time from the “host” note, and providing quick bursts of tension.

Both of these are a bit tricky to use in choral music, and often present themselves as a “cry” in the voice.

- Chromaticism: Introducing chromatic notes (notes outside the key) can create dissonance and add color to a composition. These chromatic notes would be found as passing tones, which are found in virtually any style of music, written for any configuration of voices and/or instruments. The noticeable difference between one piece and another could be the distance between the passing tone and its neighbor that belongs to the current chord. If the distance is a major second, the dissonance would be relatively small. However, if one or more half-step notes are used as passing tones, the dissonance would be quite sharp. This technique is often used to enhance emotional expression.

- Cluster Chords: These chords consist of closely spaced notes that create a rich, dissonant texture. Cluster chords can be used for dramatic effect or to create a sense of density in choral passages. For the most part, these consist of groups of whole steps, e.g., tonic, second and third steps.

- Parallel Intervals: Using intervals like seconds or sevenths can add dissonance when voices move in parallel motion. This technique can create a sense of instability and movement. This can also be accomplished using what might be called “static suspensions”, wherein a suspension like a suspend-4 would move up or down the scale. An example would be Csus4, Dsus4, Fsus4, Gsus4.

Considerations When Using Dissonance

When applying dissonance to choral compositions, it's important to consider the following:

- Resolution: Ensure that dissonance resolves appropriately to consonance, providing a satisfying musical journey for the listener.

- Balance: Dissonance should be used in moderation, balancing moments of tension with moments of calm and stability. Otherwise, the dissonances become the norm and an even more vigorous technique would need to be used to achieve a sense of tension or clash.

- Vocal Range and Blend: Be mindful of the vocal range and the ability of singers to blend harmoniously. Some dissonant intervals can be challenging to tune and maintain.

- Emotional Context: Consider the emotional context of the piece and use dissonance to enhance the narrative or mood.

Conclusion In the realm of choral music, the power and beauty of dissonant chords lie in their ability to transcend conventional boundaries and evoke profound emotions. They challenge listeners to embrace the unfamiliar, inviting them to explore the intricacies of sound and the depths of human experience. Dissonance serves as a reminder that true beauty often emerges from a harmonious interplay of opposing forces—a concept that resonates not only in music but also in the complexities of life itself.

As choral compositions continue to evolve, incorporating dissonant chords will undoubtedly remain a hallmark of innovative and emotionally resonant musical expression. Through this dynamic interplay of tension and resolution, choral music stands as a testament to the human capacity for creative exploration and spiritual connection, inviting us to listen deeply, reflect on our journeys, and find beauty in the harmonious paradox of dissonance.

Salt Cellar Creations understands the beauty and power that a Choral Group can convey and has a growing library of original works and arrangements, many of which use dissonance skillfully. Find out more about what Salt Cellar Creations has to offer for Choral Groups HERE. Explore the available music HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!