What Is Music? Is It Art?

The definition of music has been a source of discussion and disagreement for centuries. There is a technical definition of music. At its simplest, music is defined as “organized sound”. Does that mean that rap music is really music? Yes. Does it mean that Schoenberg’s tone rows are music? Yes.

Apart from a technical definition, music is perhaps one of the most difficult things to define. Is it art? Is it science? Does it have requisites? The difficulty in defining music is that there is a false idea that any music is art. Almost any series of sound, if organized, can be defined as music.

Just Music – Before we begin to explore the meaning of what music is, let’s start with a few music definitions:

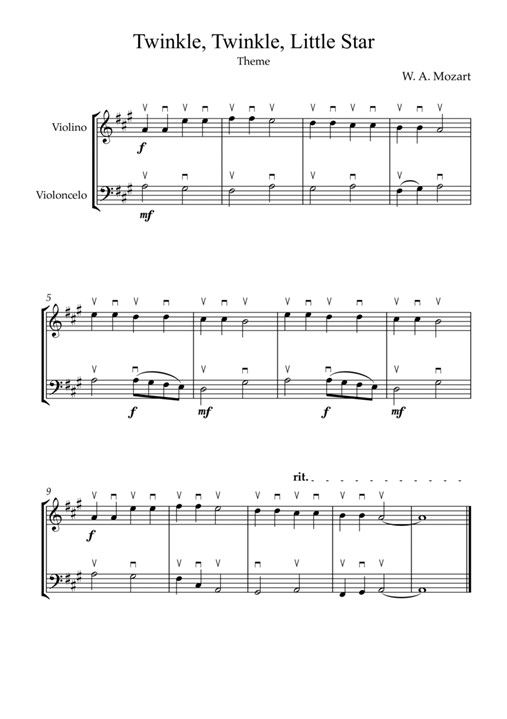

- Melody – a rhythmical and otherwise agreeable succession of tones. If a piece of music has nothing else, it has a melody. A chord progression is only an accompaniment to a melody and cannot, in itself, be a melody and cannot, therefore, be considered music. If the chord progression is being presented as music, that is, a melody, then the top note of each chord written would have to be the melody, a somewhat boring proposition. The pitch of a note refers to its highness or lowness on the musical scale; the melody of a song is the manner in which notes of varying pitches are put together in sequence. The melody is often the element that most people remember after hearing a song. A conjunct melody is smooth and easy to play, while a disjunct melody is disjointed or jumpy and more difficult to play.

- Harmony – a combination of simultaneous tones. Harmony refers to notes of different pitches played at the same time, as in musical chords. Consonance describes a smooth-sounding combination of notes and dissonance describes a combination of notes that sounds harsher. The definition of consonant and dissonant chords has changed over the centuries and is still not agreed on today. Sometimes the difference in definition is the result of a person’s musical background, location or academic research.

- Rhythm - Rhythm refers to how the time is observed and controlled in music. It includes things such as meter, which is how the beats are organized into accent patterns of strong and weak beats. Defining accents is usually done through the use of a time signature, e.g., 4/4, 3/4 or 6/8. Within those time signatures, there are a virtually infinite number of ways to reorganize the beats through the use of different length notes.

- Tempo – the speed of the beats. It also includes the general slowing or speeding of the whole piece of music.

- Dynamics - Dynamics describe the loudness or quietness of a song and the transitions between the two. Dynamics includes a number of musical terms, such as the directions “piano” and “forte” which are used in music to mean “soft” and “loud” respectively. A musician can also accent a note, emphasizing it by playing it louder than the surrounding notes.

- Tone Color - Tone color, also called timbre, refers to the way the same note can have different sound qualities on different instruments. For instance, a singer will produce a note that sounds very different from the same note played on a piano or a violin, even when they are the same pitch. Similarly, a note played in the upper register of an instrument can have different sound qualities than the same note played in the lower register.

- Texture - The texture of a piece of music refers to the number of different musical lines it has. A common musical construction has a melody line and an accompaniment. This is known as a homophonic (“same sound”) texture. Playing multiple melodies at the same time is known as a polyphonic texture.

- Form - The form of a song describes how the larger parts of it are put together; this is sometimes described as the “architecture” of the song. For instance, a single musical verse repeated over and over with different lyrics is known as strophic form. Ternary form describes a three-part piece of music in which the first and third parts are the same, but the middle part is different.

More Qualities of Just Music – The question may be, “How many of these things define music and how many are intrinsic qualities of music?” More qualities of music also includes any number of the following:

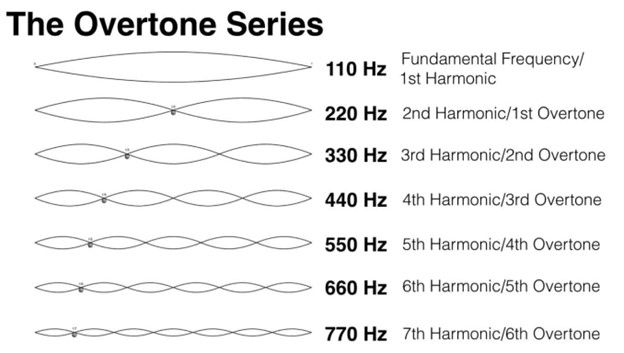

- Science – The physical means by which music is made is a science. It includes the design and construction of vocal chords and any instrument. The scales and chords that are most widely used in music are derived from the Overtone Series, a Physics and Math pattern that is embedded in the structure of material in the universe. (See the end of the article for a fuller explanation.)

- Sound and silence – Often, the silence is just a s important as the sounds in music.

- Time – Music moves through time. It cannot be perceived in a single moment. Therefore, it can be experienced, remembered and anticipated.

- Expression – Music can be a way to express oneself. It can communicate feelings, images, ideas, stories, philosophy and theology.

- Psychological experience – Music has the potential to affect and change people’s feelings, attitudes, and behaviors.

ART – Music and art are reflections of the order, variety and creativity of God’s creation. (Inspired by statements and observations of Francis Schaffer)

However, for it to truly be art, it must have two sets of things:

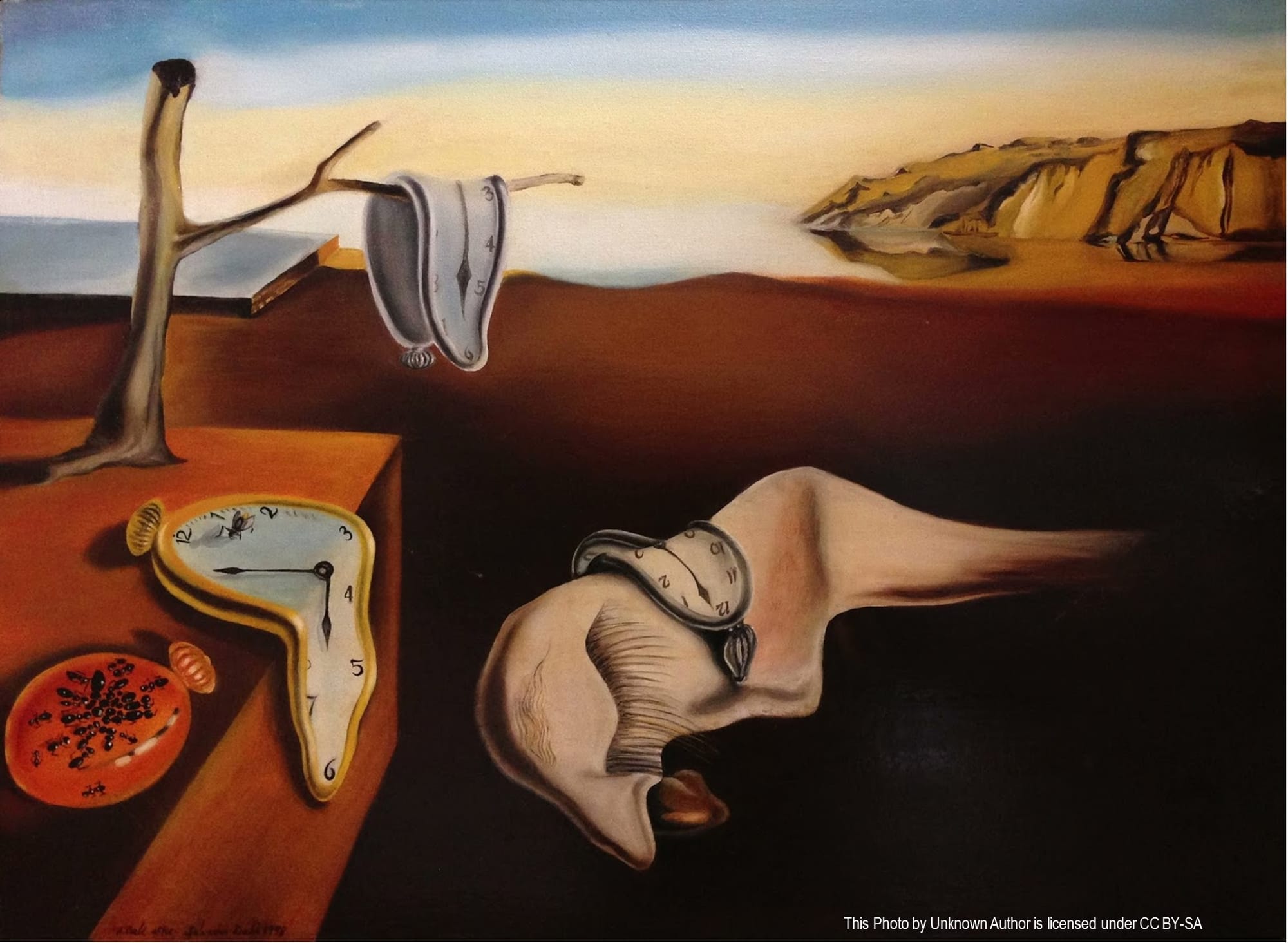

1. Tension and Release – This set of requirements applies to all art, whether it’s music, painting, sculpture or basket weaving. Without it, the creation is not artistic. In music, the composer builds tension, and then he releases it, often more than once in a composition. Even in a folk song, there may be tension and release in each verse and each chorus.

Creating tension and release can be accomplished in any number of ways. It can be done in the melody, the harmony, structure, rhythm and even silence.

- Melody – In a melody, the tension is caused by using a note that is not in the tonic chord. In the key of C, the notes in the tonic chord are c, e and g. The notes d, f, a and b would be the tension notes. The release comes when the tension note moves to a note in the tonic chord. Most commonly, the strongest release is the movement from a seventh (b) to the eighth or tonic (c). Other resolutions that cause release are from f to e, d to c or a to g. These are called Tendency Tones.

- Harmony – In harmony, a chord that contains one or more of the tension notes and moves to the tonic chord is said to have gone from tension to release. Sometimes, this is a simple movement. For example, the music goes from a G chord (a V chord) to a C chord ( a I chord), or an F chord (a IV chord) to a C chord. Another common technique for creating tension and release is the use of suspensions. These occur when a note from one chord is held over into the next, creating a temporary dissonance that resolves as the note moves to a consonant pitch. This can be used to create a sense of expectation and release. For a long time, a couple of hundred years ago, suspensions were considered far too dissonant to use even for a single beat. The acceptable way of creating harmonic tension was with the use of a Prepared Five. A chord progression using a suspension might be C | F | Gsus4 | G | C. A nearly identical chord progression using a Prepared Five would be C | F | C | G | C. G

- Structure – The way a piece is put together is called its structure. We start out with a theme, and then we develop it, giving the listener tastes of that theme, but never fully stating it. It can be presented in pieces, in a rearranged order and with some modifications. This builds tension. The tension is released when the full, original theme is stated again.

- Rhythm – The most common way to create tension and release is to vary the rhythm of the melody and its accompanying harmony and chord structure.

- And finally, one of the most overlooked methods of creating tension is silence. When we come to a dramatic pause in our music, we can almost taste the tension in the air until the music is resumed and the tension vanishes. 2. Beauty and Power – The concepts of Beauty and Power actually are very objective. That is to say, they have very definite meanings and are not left to the imagination of the one looking at or listening to some piece of art. In short, Beauty is NOT in the eye of the beholder. One can determine if the piece appeals to one’s taste, but taste does not define Beauty.

Beauty – The Bible makes it clear that true beauty comes from God, whether it’s the beauty of nature or of a godly character. The Bible includes many defining principles about God’s beauty, the beauty of creation, the beauty of wisdom, human beauty, and even beauty that’s misused by the ungodly.

Here are a few examples:

- He (God) is altogether beautiful in His temple (Psalm 27:4; Isaiah 33:17).

- All that God made was and is good and He is to be praised for His magnificent handiwork (Genesis 1:31; Psalm 19:1; Ecclesiastes 3:11).

- Wisdom is beautiful, “more precious than rubies,” and it leads to peace, life, and blessing (Proverbs 3:15-18).

- Because mankind was wonderfully created in God’s beautiful image, we should not allow others to define beauty for us (Genesis 1:27; Psalm 139:14).

- Nature gives us an example of true beauty in the splendor of God’s creation (Matthew 6:28-29).

Power – Power can be defined as the ability to influence people and events. It can also refer to a form of energy or a mathematical concept or function. As it applies to art, it means the ability of the music itself, with or without lyrics, to influence the emotions and thoughts of the listener. Great lyrics embedded in an insipid piece of music does not constitute powerful music. Power can be achieved a great number of ways, but, more often than not, the music must include number of things, including (but not limited to):

- Variety – There must be some sense of variation in the melody and/or harmonies.

- Motion – Variety is closely related to Motion. A consistently conjunct or repetitive melody has no motion. A powerful car is considered to be powerful only if it is seen in motion.

- Tension and Release – The tension and release mentioned earlier must be designed in such a way that it makes the thoughts and emotions soar; it shouldn’t be perceived as only an academic exercise.

- A Decisive Cadence – The most common of decisive cadences is Dominant to Tonic (V to I). However, some music doesn’t lend itself to that sort of cadence, but no matter the style, the should be “closure” to the piece.

In Conclusion, there will still be discussions and disagreements about what makes music and what makes musical art, but there should be much more common ground once it is understood that the decision is not purely a subjective one. Here are some quotes from famous musicians and others:

- One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain. - Bob Marley

- If music be the food of love, play on. - William Shakespeare

- Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything. - Plato

- Without music, life would be a mistake. - Friedrich Nietzsche

- He who joyfully marches to music in rank and file has already earned my contempt. He has been given a large brain by mistake, since for him the spinal cord would suffice. - Albert Einstein

- Next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world. - Martin Luther

- Beautiful music is the art of the prophets that can calm the agitations of the soul; it is one of the most magnificent and delightful presents God has given us. - Martin Luther

The Overtone Series

The scale, notes and chords we use weren’t invented by anyone. The notes we use come from a mathematical formula imbedded in the way a string behaves when it is struck or plucked. When a string vibrates, it sets up a wave along its entire length. It also sets up two waves at exactly half its length; three waves along exactly one third of its length; four waves at one fourth its length, etc. There is a point at which the string doesn’t set up any more waves, depending on its length and thickness, but the human ear can’t detect any notes created by the waves at one sixth or seventh of the string’s length.

The notes created by these waves are the ones that are in the chromatic scale. Without getting too technical, if you held down the “loud” pedal on a piano and hit a low C, you would also hear the C above that, the G above that, then the next C, the E, the next G, the A and the B-flat. You may have noticed that all of those notes are found in common variations of a C chord. If you tried all of the notes on the piano, you would only find the notes in the chromatic scale, nothing in between.

When the harpsichord and other early keyboards were invented, they reflected those notes in the black and white keys. Even before that, when music was written for Gregorian chants, all they ever used were those notes.

People discovered the way God had created the musical scales. We have modified, rearranged and tinkered with scales, but we could only use what God had created for us.

At Salt Cellar Creations, we have written, arranged and performed a wide array of music styles, and all of our music meets the definition of art. We skillfully use the elements of composition and arranging to craft our music. We have a growing library of original works and arrangements for your ensemble to experience. Explore the available music HERE.