Inside a Great Arrangement – Part Two

In the first installment in this series, we looked at Arrangements for Recording Pop Music and Arrangements for Live Musicians. In this second installment, we will look at some Samples of Variations in Arranging and two of the Arrangement Elements for More Professional Arranging, Key and Motif.

Samples of Variations in Arranging

Even if the arranger knows all of the ins and outs of all of the instruments and voices, he or she must know how to best assemble them. There are a dozen ways to arrange any song or piece of music. I have done some variations of the hymn AmazingGrace.

- Long ago, a group I was in did it in 4/4 with some 50s rock and roll chords. It was fun and helped people to hear the words better in that different setting.

- Lately, I’ve written it in 5/4 for SATB choir with some alternate jazz-type chords. It’s called Now I See. I’ve also done a verse of it in a minor key; that set off the somber tone of the lyrics of that verse.

- I have also arranged it in 4/4 for SATB A Capella choir, but the rhythm of the melody is “straightened out” to be mostly quarter notes. With simple chords, the whole sound is very Appalachian. It’s called How Sweet the Sound.

Let’s look at another example of how to arrange a piano / keyboard part. I’m going to describe a general placement of notes. This is called Voicing.

- Chords in which the notes are placed close together tend to sound as if their energy is being confined. It’s great for a while, maybe a long phrase or even a verse of a vocal piece. If the whole song is done that way, the energy dies. If the energy is allowed to escape, or even explode, the song has life. This is done by moving the notes farther away from each other. This can be done slowly or quickly.

- Chords in which the notes are farther apart let the energy out; they sound more powerful and exciting. But, if the whole song is done that way it becomes like A TEXT MESSAGE THAT’S ALL IN CAPS. No one likes to be shouted at all the time.

- There are a number of ways to voice a chord besides simply bunching or spreading out the notes. If you have a D chord and the D is on the bottom, it sounds the strongest. If you put the third of the chord (F#) on the bottom, it’s a good way to “lead the ear” to other chords. When the fifth (A) is on the bottom, it makes for a warmer sound or can prepare the ear for an A chord.

- For a rock and roll version, the piano player would bang out chords near the top of the treble clef while the left hand would wander around the low end of the bass clef. For certain parts of the song, he might even use open, or power, chords to give the sound even more “space”. This gives the song a “big” sound and adds to the brilliance of it by turning the piano into two virtual instruments.

- For a piece with jazz chords, the chords might start out bunched up a bit, then spread out as the song progresses. This general type of voicing could be designed to emphasize whatever the lyrics might be saying at the time. This bunch /expand pattern also tends to turn this into real art instead of just music. Here’s the article about Just Music or Art.

- The minor key version might be played a little lower on the keyboard. This takes advantage of the way the listener perceives the music. The lower register, even if it was in a major key, would sound more somber.

- An arranger could use multiple keyboards – real piano, electric piano, electronic keyboard. At least one would be rhythmic and the other(s) would be pad, or fill-in, sounds. For this, the chords could be bunched up AND expanded on different keyboards. The difference between this arrangement and the others would be that to make art of the song, one or more keyboards would drop out and come back in at different times. This is known as terraced dynamics and was developed in the time of Johann Sebastian Bach. Organists and electric guitar players still use it today.

The main point here is that arranging is a way to make a song (whether vocal or instrumental) sound its best. It’s also a way to help convey the intention and emotion of the composer or performer. And, it’s not a simple process.

Before an arrangement of someone else’s work can be done, there must first be a good song to arrange.

Soon after the Beatles broke up (If you’re not sure who they were, try YouTube), you could still find their music all over the place, in elevators, restaurants and grocery stores. But, it wasn’t them playing and singing; it was instrumental arrangements of some of their songs. There were string quartets and wind ensembles playing Yesterday and Eleanor Rigby. Why? Because they were well-written pieces of music with good motifs and forms and interesting chord progressions.

There is a song by Christian musician Randy Stonehill called Shut De Do, a Jamaican-ish sounding song that, although not that complex, has been arranged for everything from church choirs to steel drums to hand-bells to glass harp. Why? It’s a great piece of music.

Arrangement Elements for More Professional Arranging

Once a song worth arranging is found, the next thing to do is to have a good understanding of things like key, motif, form and the ensemble for which the arrangement is being done. This section is a discussion of the first two of those four things. The other two will be discussed in the final installment.

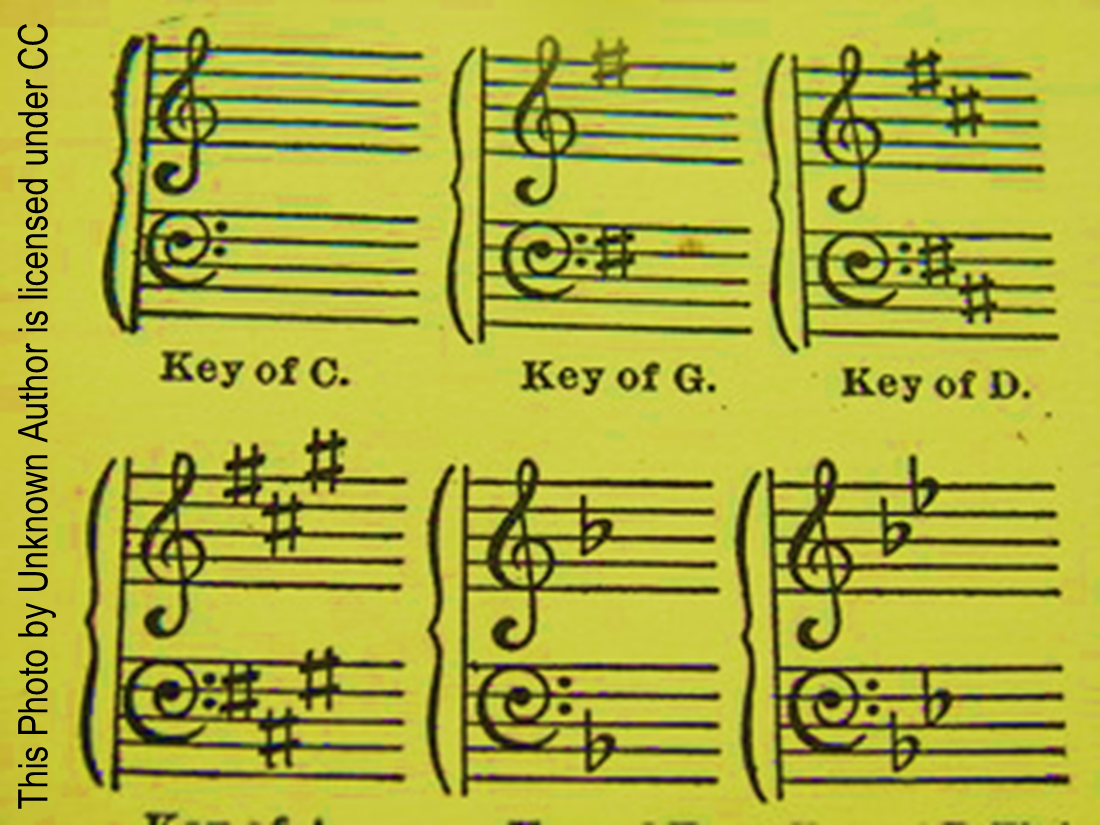

KEY

There are general rules in music to find the key. But, some music isn’t in a key, as many people think of keys.

- Most music after about 1750 has been written in either a major or minor key. Even though the key signatures of a song in a major key and a song in a minor key may look the same, there are significant differences between them. There will be another article all about Keys later.

- Some music is written in modes. Modes existed long before keys. They weren’t major or minor; they were just modes. Bagpipes, lap dulcimers and some ocarinas often play in modes.

- Some music is written in a pentatonic scale. This scale has only five (penta) notes (tones). The song Amazing Grace is in a pentatonic scale. A lot of Oriental music is pentatonic, like a Japanese pop tune, famous in the USA from the 1960s, called Sukiyaki.

- Then, there are things like the Schoenberg 12-tone Scale, a culmination of so-called intellectual music. In short, it is an arrangement of the twelve semi-tones of a single octave into a melody (e.g. d, f#, bb, g, c#, a, eb, c, e, ab, f, b).

In short, the key, whatever it might be – major, minor, modal, pentatonic or 12-tone – offers the listener a home for the ears and most songs end on that home chord (called Tonic). Occasionally, a composer will end a piece of music on a chord other than tonic.

The chord progression that precedes the end of a song or a section of it is called a cadence; it indicates a partial or full “resting place”. Sometimes these progressions can lead the listener to somewhere other than a cadence in the song’s key. These can be a half cadence (e.g., ending a song that’s in the key of G on a D or C chord) or even a deceptive cadence (ending a song in G on an E or B chord). An original piece for Concert Band in Salt Cellar’s catalog called Rockin’ Rondo does just that.

Speaking of chords, a rough calculation indicates that, for any one single note, there are at least 180 different chords that include that note. Only a dozen or so are worth using; the others are purely academic. But, still, knowing which ones are available and how to use them is extremely important. Music gets very boring if the same chords are used over and over and over and…

Think of alternate chords and progressions as adventures in a piece of music – going the scenic way home. Sometimes a word or phrase in a song needs some emphasis – a different chord or progression can do that. But, like everything else, alternate chords need to be used judiciously. Just the right number and placement creates wonderful splashes of color on a backdrop of a “normal” chord progression. Too much color creates a new backdrop where nothing stands out. Imagine a painting with splashes of orange as an accent. But, if an artist uses a splash of bright orange on a painting that’s mostly orange already, his “splash” of color gets lost.

Choosing a good key for a piece of music can be a challenge. Different instrument families prefer different “key families”; that is, some instruments prefer sharps while others prefer flats. We will discuss that in depth in the third part of this series.

Final word – maybe a warning to some – about keys. The key of a song is not a ball-and-chain, a prison or a restriction of any kind. It’s home and home is always nice to go back to, but sometimes you end up somewhere else. There are things like a modal insertion or secondary dominant that can add great color to music without detracting from its original key center.

MOTIF

The Motif is the pattern of the important part(s) of the song. A good song or other piece of music has a number of motifs. If the music has no recognizable motifs, listening to it is like watching a cat wander around; it’s usually pretty boring. Having good motifs is important if you want your song to be memorable.

There are melodic and rhythmic motifs. Chords usually don’t create motifs, although they might in some situations. In those situations, a chordal motif would most likely be a combination of melodic and rhythmic motif elements.

A melodic motif defines what direction the notes go – up, down, up then down, conjunct (smooth), disjunct (angular), etc. Just as when a piece of music is in a key and the composer / arranger uses chords not normally found in that key, so a melodic motif can be altered. In the two choral arrangements mentioned above, the new time signature required a modified melodic motif as well as a new rhythmic motif.

A rhythmic motif is just that, the definition of the rhythm that the music takes. There may be one for the melody, one for the harmony and one for accompaniment instruments. For guitarists, this is often referred to as the strum pattern. Again, a rhythmic motif can be altered to emphasize or restate that motif.

When altering a motif of either sort, a composer / arranger should be sure to keep the new motif consistent, at least for the section in which it was introduced. Rarely, the new motif can be overlaid against the original in some contrapuntal pieces, but it can be difficult.

In the next and final installment of this series, we will explore Music Forms and Writing for a Particular Ensemble. There will also be a section ion how to Apply all of this info, as well as an interesting section on the Overtone Series. No one invented music; it is part of God’s creation and contains mathematical and physical science properties.

Salt Cellar Creations skillfully use the elements of composition and arranging to craft its music. We have a growing library of original works and arrangements for your ensemble to experience. Explore the available music HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and New Zealand. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!