How to Add Spice to a Choral Arrangement

Choral music can be very expressive, exhibiting the best of musical composition and arrangement. However, there must be a sense of art about the piece. Otherwise, it’s just so many notes. For more information about what makes a creation of any sort truly a work of art, whether it’s music, a visual piece or some other craft, read the article Is It Art or Just Music?.

Spice, of course, is a word more associated with food than music, and, as there are a myriad of flavors provided by each spice, so there are myriad ways to add spice to music of any sort.

It’s that certain something, that je ne sais quoi that makes the music sparkle and be memorable. Brass instruments can have a lot of spice. They can attack, sforzando, be muted three different ways, and use a tongue trill or vibrato. Woodwinds tend to be more smooth and schmaltzy, but they can sound flashy with their flutter tonguing and overblowing to play super high notes. String player have a variety of ways to use the bow and their fingers to achieve an assortment of different sounds. Most singers get very upset when someone puts a mute in their mouth or shakes them to make their voice different. So, what can be done for voices? While the actual sound of the voices in a choral group can’t be altered a lot, the way the music is written can offer a plethora of variations to the music.

Unique things That Have Already Been Done –

- In the 1920s, a few classical choral scores called for speaking instead of singing their parts, including some shouting, hissing and raspberries. This speaking-instead-of-singing technique was first called rapping in the 1950s and 1960s, but without the hissing and raspberries; the style was later revived and altered in the 1980s.

- Some classical composers wrote part that were somewhat atonal, singing “around” a note but not quite on it, almost as if it were the perceived sound of a ghost.

- Of course, a choir can always clap, snap, stomp and sway, play tambourines, finger cymbals, and hand drums. But, those devices, though effective in their particular songs, have lost their uniqueness. Some choral groups have added outright dancing to some numbers, but that doesn’t really affect the music.

Adding Spice to an Existing Piece – Surprisingly, some of the most useful devices to add spice to a choral arrangement are to perform it properly. Indeed, to add spice to any choral or instrumental piece requires that it be done with precision. When a group of singers starts and ends a word at the exact same time, it adds a certain crispness. When the words are pronounced the same way by everyone (even if it’s an incorrect pronunciation done for some effect), it adds clarity and transparency.

Everything should be done the way the composer or arranger indicates, including dynamics, tempo, expression and technique. The comparison between improper and proper performance is the difference between mumbling and sparkling elocution.

But, even if a choir does ALL that, if the music isn’t good, then they’re, well, wasting their breath. An arrangement worth singing has to have a few essential characteristics.

CREATING A BETTER ARRANGEMENT

The essential thing in a choral arrangement with spice is variety. A simple method is to have each part sing a different verse. More involved techniques involve arranging the song so that the chord progression or meter for different parts of it would be a bit different. The dynamics, tempo and/or expressions also can be varied. Here are a few guidelines that an arranger might use to add just the right amount of spice to a choral arrangement or composition.

- CHORD PROGRESSION – There are hundreds of possible chords that can go with any one note, but only a few that really sound acceptable. A good “marriage” of lyric tone (happy, sad, angry, etc.) in a certain passage and a chord progression can really beef up that passage.

The variety of chord progressions used in any one song should fit in a determined category. A good choral arrangement wouldn’t usually have tight jazz chords and open modal chords in the same piece, unless it had a certain story to tell that would benefit from such a wide array of progressions.

It's also possible to use a different chord progression under an identical melody to give the song some spice. This may prove a bit difficult, especially if the song is well-known and the chord progression is expected. If that’s the case, a few well-placed variations on a chord may be the answer, such as suspensions, major or minor sevenths, or adding a 2 or a 6. They would add some color and / or movement without actually being a different chord. - VARIATION ON THE MELODY – In addition to, and maybe as part of the procedure of using appropriate chords, occasionally an arranger will use an escape tone or passing tone to add a bit of spice to the melody. A lot of soloists do this as part of their performance. The arranger would simply make it part of the “official” music. Doing one of these will tend to reinforce the motion of the melody, not change it.

- VARIATION ON THE HARMONY – It seems logical that in cases when the chord progression can’t, or shouldn’t, be changed that the harmony would need to stay the same. However, the harmony can often be rearranged in such a way that it sounds a bit different withing the structure of the chord progression. This can be accomplished through the use of different voicings.

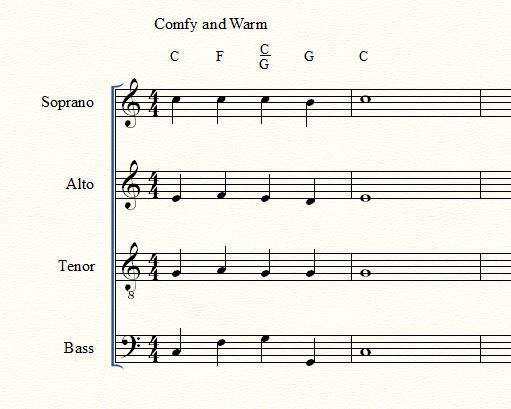

Here are three simple examples of how the same chord can be voiced for an SATB choir. The first (below) is a simple, comfy and warm rendering of a common chord progression, It’s in C major. The third chord is called a Prepared Five; it’s a forerunner to the suspended four that is used (too much) today. In this example, notice that the soprano and bass both start and end on a c note. That establishes the chord progression strongly. The alto and tenor parts and spaced evenly between the soprano and bass. That makes for a full, rich sound.

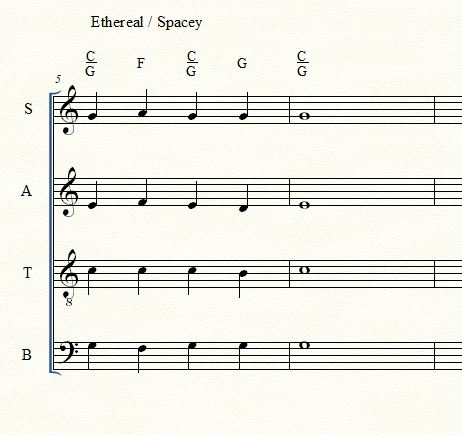

The second example (below) contains essentially the same chords, but the voicing makes it less settled. Notice that the bass part starts and ends on a g note, even though they are C chords. That gives the progression a somewhat ethereal or spacey sound, not quite grounded. The other parts are also closer together, with the soprano part also starting and ending on a g note. The tenor is the only part that starts and ends on a c.

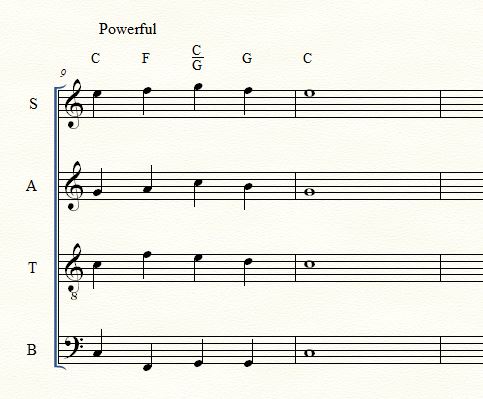

The last example (below) has the identical chords as the first one, but the voicing is spread out farther. Notice that the bass starts and ends on a c, and its range is lower and farther away from the rest of the voices. Also notice that the soprano starts and ends on the high e, emphasizing the major-ness of the chord. The alto and tenor parts are a bit higher in their ranges and add more brilliance to the sound.

- METER – In movie and TV music, you may hear the theme song played in a different meter. That is, the arranger would take the strong rock-ish theme in 4/4 and play it with strings in 3/4 for a sentimental part of the show. The same thing can be done in vocal music. Often, this is done for the whole song, but it can be used the same way as using an alternate chord progression to reinforce a lyric tone. Salt cellar creations has a unique arrangement of Amazing Grace called How Sweet the Sound that does just that. It’s in 4/4 time, the melody is recognizable but not exactly like the original, and has a very Appalachian sound about it. We also have “Now I See”, another arrangement of “Amazing Grace”, but this one is in 5/4 meter and has some jazz chords in it.

- DYNAMICS – Virtually ALL of contemporary music, pop, rock, country, and contemporary Christian is compressed when it is mixed/mastered. This is done with a device that basically makes the softer parts louder and the louder parts softer so that there are no real noticeable dynamics. It’s produced to be listened to by people doing something else besides really listening to the music.

To make a choral arrangement stand out, it NEEDS variations in volume. Life has sound levels; so should music. Some parts of a song are intimate, some are worth sharing loudly. Also, sometimes these dynamic changes can be gradual and almost imperceptible so as to build some tension. At other times, a sudden cloudburst of sound can introduce a powerful lyric passage, or a subito piano (suddenly quiet) can introduce an intimate or secretive line of the lyrics. - TEMPO – When you get excited, your heart rate goes up. If a song is getting exciting, it can speed up, too. If it gets pensive, it can slow down so the listener can think along with the words. An arranger or composer must use caution here; it can be easy to speed or slow a song too much in an effort to be expressive. For music being written or arranged for some less experienced choral groups, it’s a good idea to include an easy way to change tempo, especially if it’s a sudden change. Include a fermata or rallentando that can allow the conductor to indicate the new tempo inside of the slow-down. A full measure of rest can also be used for the same purpose.

- EXPRESSIONS – Some people, when they are in deep, poignant discussion (argument) with someone will poke a finger at the other person’s nose. A great choral arrangement can make a point with “pointed” notes such as staccato and accents. Alternately, a sweet song should be silky smooth. An arranger can achieve such silkiness by using close harmony, some parallel motion or effectively placed slurs. The best ice cream sometimes includes nuts and chocolate chips among its creaminess. So, too, the best choral arrangements have a proper balance of expressions.

- LAYERING – Layering can be achieved in a few different ways. One way is by using polyphony. It’s not just harmony, but a concept in which different melodies are sung at the same time. The chord progression fits both melodies.

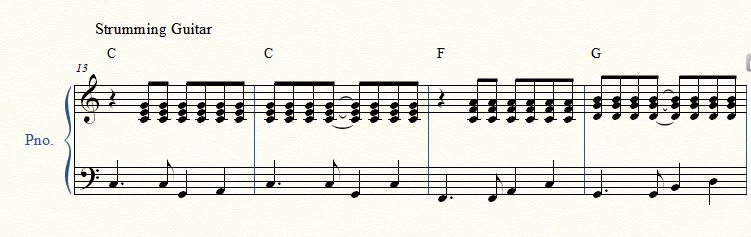

It can also be done with staggered entries. Each part comes in at slightly different times, but all end at the same time. The parts have to be modified so that while the early entries are “waiting”, they still sound like they belong. We have an arrangement of “He Who Would Valiant Be” from John Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” with some layering. It’s not quite polyphony, but it’s interesting enough for a choir of high school aged singers. We also have an unusual, ethereal arrangement of Silent Night called “Silent Night (Song of Light)” that has some polyphony toward the end of the piece. - VARIATION ON THE ACCOMPANIMENT – Sometimes, especially when arranging a popular tune, the arranger will be faced with a challenge in that the original accompaniment part was a rock or country rhythm section (guitar, bass, piano and drums). Since all the composer / arranger has to work with is a piano, all of the essential elements of the original sound should be included. Often, this means “thinking outside the box”. A strumming guitar can be duplicated a number of ways. Below is a sample of one way.

- If the original was a piano ballad style accompaniment, that is easy enough to duplicate. However, if there was a drum kit or guitar behind the piano, the accompaniment may have to include a little more rhythm, possibly in the left hand. Below is a sample of that method.

- A more “airy” type of accompaniment is one that uses arpeggios to create that feeling. It can be used to add some rhythm from the original music without being too heavy. Here is an example of that style.

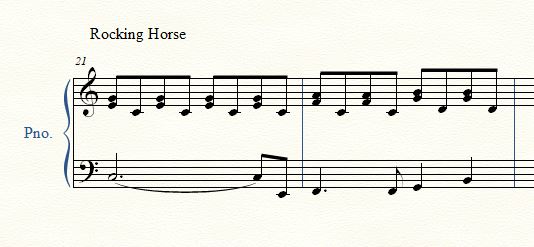

- Still another style is what I call the rocking horse. It has a bit of the feel of a piano ballad, but with a little more movement to it. Some guitar players who pick using a folk style picking pattern will use this, which, if its part of the original music, makes the transition to piano more reasonable. Here’s what the Rocking Horse might look like.

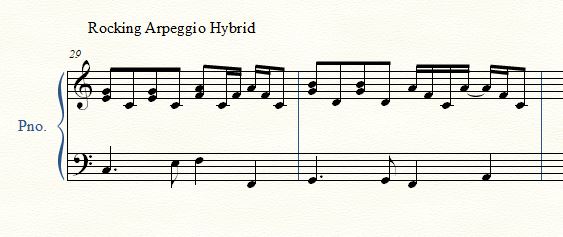

- One more style is really just a hybrid of the Rocking Horse and the Arpeggio styles. Musicians like Elton John used this to create a sound that sounded more difficult to play than it really was. Here’s what the Hybrid could look like.

- Most choral arrangements have a piano part as the accompaniment because that is all that permitted in choral competitions. The reason that there aren’t a set of alternate accompaniment parts for regular concerts and another for competitions is that once a choral group learns a piece with one accompaniment part, with its particular setting and cues, it can be difficult to acclimate to a different accompaniment.

This list is not exhaustive, but gives you a good look at what an arranger needs to do to give a choral piece the SPICE it needs.

Salt Cellar Creations understands the beauty and power that a good choral group can convey and has a growing library of original works and arrangements to help accomplish those goals. Find out more about what Salt Cellar Creations has to offer for Choral Groups HERE. Explore the available music HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!