How Many Parts is "Too Many" in a Classical Composition?

As a foreword - This was originally written about concert band music, but it can apply to choral, orchestral (of any type), rock and other kinds of music. Also, this article will focus on what is commonly called classical music, although it’s used to describe any type of serious music.

One of W. A. Mozart’s patrons, Emperor Joseph II, supposedly said, “Too many notes, dear Mozart, too many notes” after the first performance of Mozart’s Entfuhrung aus dem Serail in Vienna's old Burgtheater. Mozart's reply reportedly was, “Just as many as necessary, Your Majesty.”

In the realm of music composition, the question of how many different parts should be included in a classical composition is one that has sparked debate for generations. Should a composition be richly layered with numerous instruments, each playing a unique role, or should it strive for simplicity, with fewer parts ensuring clarity and precision? This debate, while complex, is fundamental to the world of music. In this opinion piece, we will explore the various facets of this discussion and consider whether there can indeed be too many different parts in a classical composition.

Origins of Multi-Part Music

In the early years of the Middle Ages, two types of vocal music were dominant, the Gregorian and Gallican chant, both used primarily for Christian worship. There was a limited amount of instrumental music written during that period, mainly for woodwinds like the flute, pan flute, and recorder; string instruments like the lute, dulcimer, psaltery, and zither; and brass instruments like the sackbut (similar to the modern trombone). Troubadours would accompany themselves on a simple stringed instrument such as a lute or psaltery.

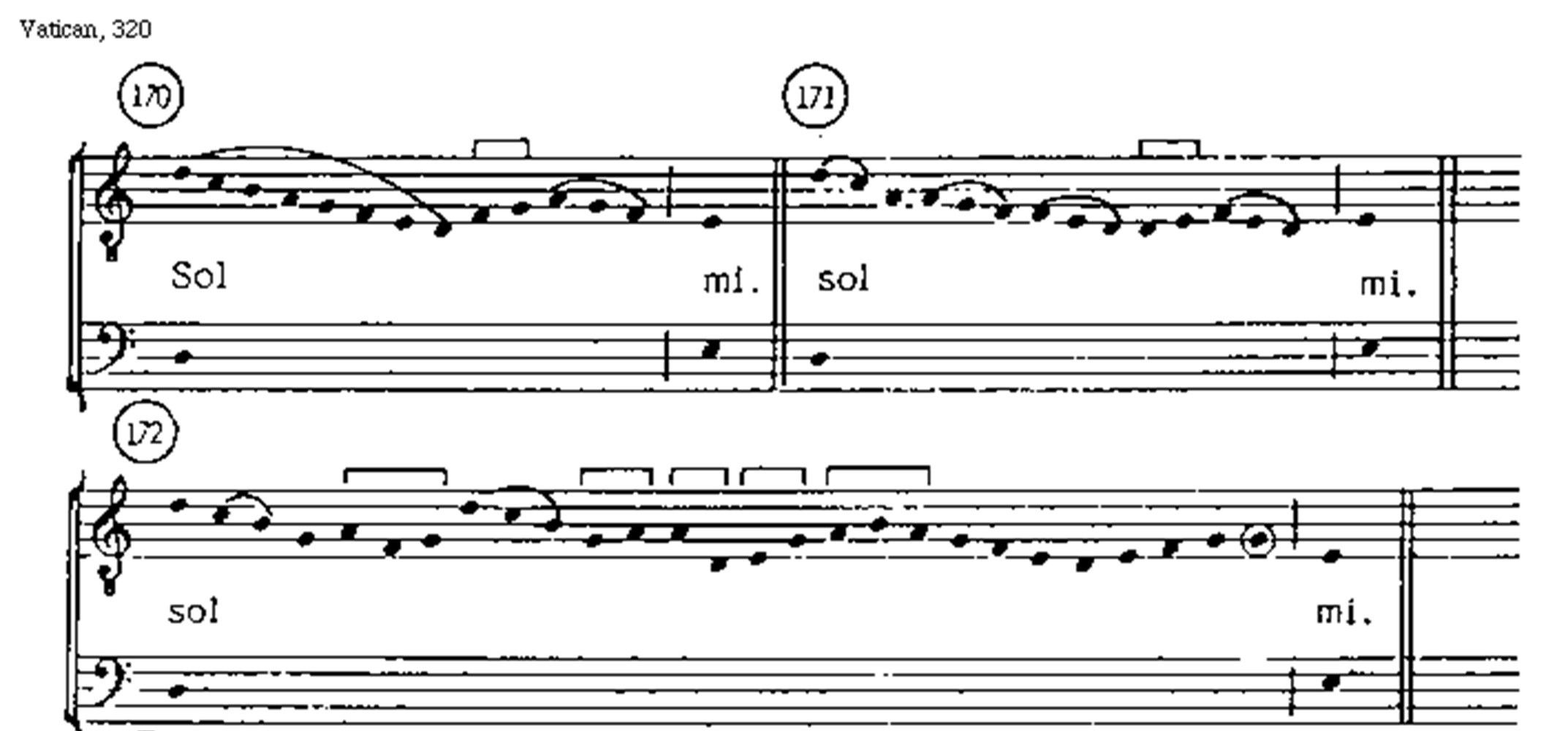

In later years, a form of music known as organum was introduced. It was two melodic lines moving simultaneously, sometimes creating an imaginary chord. Sometimes a second, or organal, voice doubled the principal voice at an interval of a fourth or a fifth below. It was for both vocal and instrumental music. This method increased the likelihood of creating a true chord.

A French composer named Pérotin was among the very first to compose organa (plural for organum), the earliest type of polyphonic music. Before Perotin began composing his particular style of organum, generally consisted of two voices, called organum duplum. Not satisfied with just two voices, he began composing organum triplum and organum quadruplum, which were polyphonic pieces with three and four-part polyphony. His Sederunt principes and Viderunt Omnes are among only a few organa quadrupla known.

A prominent feature of his compositional style was the tenor. The tenor is based on an existing melody from the liturgical repertoire. In the various forms of organum that were developed in Paris, the tenor holds the melody (from the Latin tenere, meaning “to hold”) of the Gregorian chant. This part will be sung in long, held-out syllables, laying an organ-point or harmonic basis for the additional lines which will have many notes to each note of the tenor.

During this time, the church imposed strict rules about what kinds of musical devices could or couldn’t be used. For example, all music in the church was to be in triple meter. And the tactus, the basic beat of the music, was to be at 60 beats per minute, the pulse of the heart at rest, so that the music would be peaceful. However, that didn’t stop composers from bending the rules. Triple meter can be subdivided a number of ways so that the tempo appears to be faster and the music can take on a more lively sound.

John of Salisbury (1120–1180) taught at the University of Paris. He was also a philosopher and Bishop of Chartres, and attended many services at the Notre Dame Choir School. In De nugis curialiam he describes what he perceived was happening to music in the high Middle Ages. He is quoted as saying, “When you hear the soft harmonies of the various singers, some taking high and others low parts, some singing in advance, some following in the rear, others with pauses and interludes, you would think yourself listening to a concert of sirens rather than men, and wonder at the powers of voices . . . whatever is most tuneful among birds, could not equal. Such is the facility of running up and down the scale; so wonderful the shortening or multiplying of notes, the repetition of the phrases, or their emphatic utterance: the treble and shrill notes are so mingled with tenor and bass, that the ears lost their power of judging. When this goes to excess it is more fitted to excite lust than devotion; but if it is kept in the limits of moderation, it drives away care from the soul and the solicitudes of life, confers joy and peace and exultation in God, and transports the soul to the society of angels.”

His attitude about moderation applies well to today’s church music.

As time passed, more parts were added and the rules were ignored or removed. Some of the resulting music was extremely complex and sometimes, as in vocal music, unintelligible to the listener, though beautiful to listen to. Soon, some composers and musicians started asking themselves, “How many parts is too many”?

The Beauty of Complexity

One argument in favor of composing with a multitude of parts is the richness and depth it can bring to a piece of music. In the hands of a skilled composer, a classical piece with a wide array of instruments can create a sonic tapestry that is both intricate and captivating. This complexity allows for a broader palette of sounds, enabling composers to convey a wide range of emotions and moods within a single composition.

Moreover, the beauty of complexity in music lies in its ability to surprise and engage the listener. When numerous instruments interweave and interact, it can lead to moments of revelation and excitement. Each part contributes to the overall texture, and the audience may find themselves discovering new nuances with each listening.

The Challenge of Balance

However, the proponents of simplicity argue that too many different parts can lead to a lack of clarity and coherence in a composition of any sort. Classical music, especially those ensembles with the capacity for many parts, can fall victim to the temptation to assign different parts to each instrument or section.

Balancing a multitude of instruments, each with its own unique timbre and role, can be a daunting task for a composer. If not managed effectively, the result can be a cacophony rather than a harmonious piece of music.

Furthermore, a composition with too many parts can overwhelm the musicians themselves. It requires a high level of skill and coordination to execute such pieces successfully. Inexperienced or less proficient musicians may struggle to keep up, leading to a performance that falls short of the composer's intentions.

In order for the music to be able to be communicated to the listeners, it must be understandable to the performers. And, it must be satisfying to those performers to be able to properly interpret and recreate the music on the page. Some music may be enjoyable, even fun, to perform, but it has to have some redeeming quality to it for the singers and/or players.

The Listener's Perspective

Ultimately, the success of a classical composition is often measured by the experience it provides to the listener. From the listener's perspective, the question becomes: does the complexity of a composition enhance or detract from their enjoyment?

For some, the challenge of unraveling intricate compositions is part of the allure of classical music. They revel in the layers of sound and the puzzle of identifying each instrument's contribution. These are listeners who are very actively listening to the music. They would rarely have music on as a background to their other endeavors since they consider listening to the music to be the primary activity. In this sense, complexity is not a barrier but an invitation to deeper engagement.

Conversely, others may find themselves overwhelmed by compositions with too many parts. They long for the simplicity and clarity that comes with fewer instruments. Many would deem a piece of music to be good if it made them feel good. Music would also be a backdrop to a more important activity. To them, music should communicate directly and immediately, without requiring exhaustive analysis.

Finding the Balance

So, can there be too many different parts in a classical composition? The answer is not a definitive yes or no but rather a matter of balance and intent. The key lies in the composer's ability to harness complexity without sacrificing clarity and in the performer's proficiency to execute the composition faithfully.

It's essential for composers to approach complexity with a clear artistic vision. Each instrument and part should have a purpose within the composition, contributing to the overall narrative or emotional expression. In this way, complexity becomes a tool for artistic expression rather than an end in itself.

In the case of vocal music, it may be wise to err on the side of simplicity so that the words can be understood; it is, after all, the main reason for writing a vocal piece. However, sometimes, if a piece of music, or its words, is well-known, an arrangement can use staggered entrances to give the music more texture while being fairly sure that the words won’t be lost in the music.

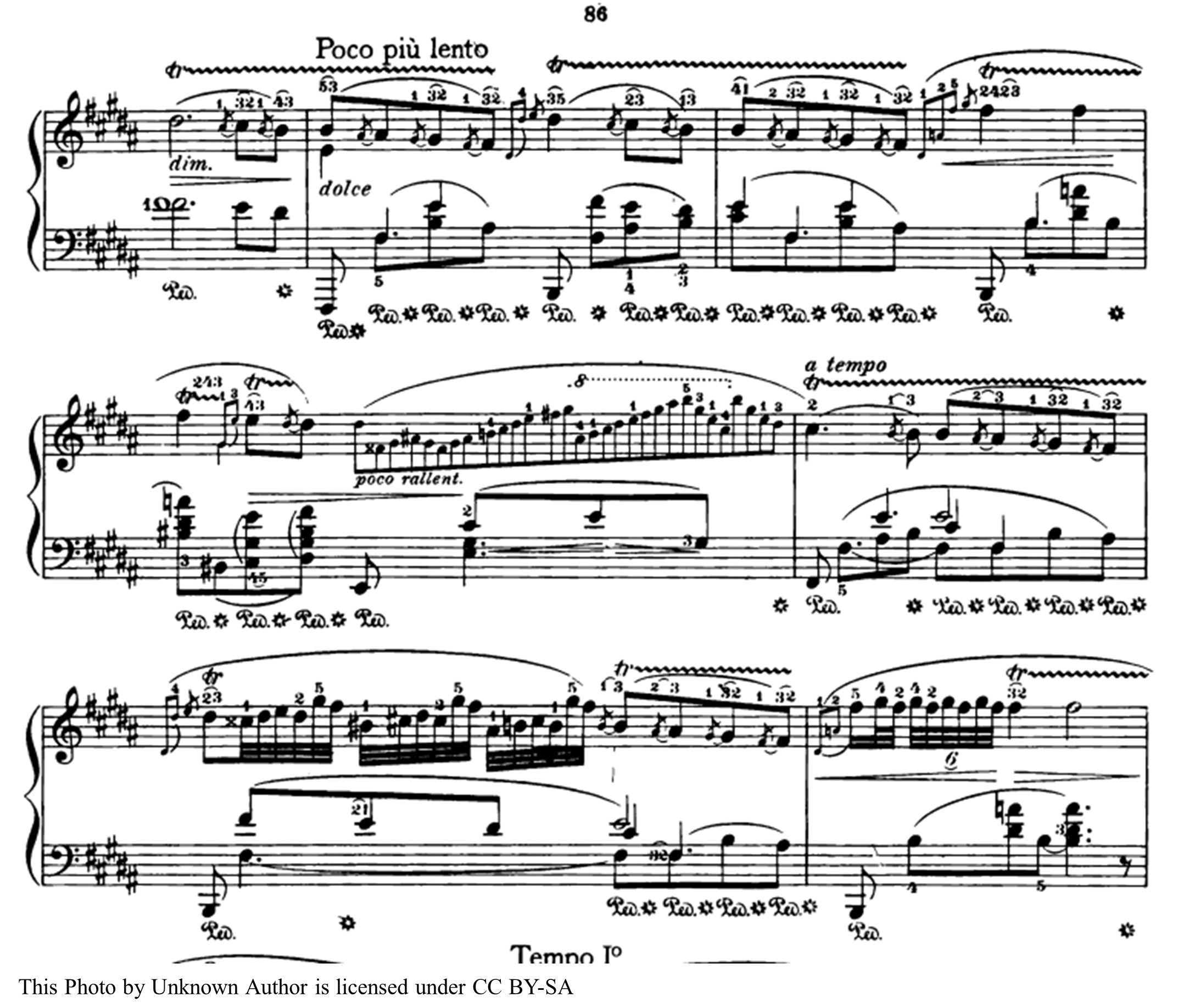

For instrumental music, a severely complex piece may depict the very emotion or message that the composer wants to present. The severely stacked chord near the very beginning of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor is an excellent example of a single chord’s extreme complexity. Any music with either a complex chord or lines of fugal-type melody should, for the sake of good art, resolve itself at some point, which is what Bach does a number of times in the Toccata mentioned above.

The Performer’s Ability

It may appear to be apparent, but the appropriateness of how much complexity should be in a piece of music, especially when young musicians are involved, depends on the skill level of the ensemble. A middle school-aged concert band may well have only one part per instrument; that is, one part for all flutes, clarinets, trombones, etc. The complexity could not be very deep at all.

A Personal Story – When I was in sixth grade and had played the trumpet for only a couple of years (band started in fourth grade then), the sixth grade band members were invited to join the junior high band in playing for the town’s memorial day parade. We played an old (now out of print) marching band song called The Aquanauts that was written for a band such as ours. However, despite having only one part per instrument, it contained some wonderfully simple bits of complexity, very appropriate for a beginning band. Being able to play such rudimentary complexity gave the band members a very definite sense of accomplishment and was easy for the audience to hear and appreciate.

If the high school marching band had been asked to play the same thing, a fair number of us would have taken immediately to improvising assorted extra parts while playing with our eyes closed. Obviously, a high school band needs a lot more difficult music into which they could sink their teeth.

Musicians, regardless of age, need to have music that fits their experience and dedication to music. Some students take music class more for a lark that an affinity for music. Simply put, performers must be up to the challenge presented by complex compositions. Rehearsal, precision, and a deep understanding of the composer's intentions are crucial in ensuring that the richness of the music shines through without becoming overwhelming.

Conclusion In the world of classical composition, the debate over the number of parts a piece should have will likely continue. While some composers will continue to craft intricate and multi-layered compositions, others will opt for simplicity and clarity. Both approaches have their merits and can create deeply moving and memorable music.

Ultimately, the beauty of music lies in its diversity. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to whether there can be too many different parts in a classical composition. Instead, the measure of a composition's success lies in its ability to connect with its audience, whether through complexity or simplicity, and to convey the composer's artistic vision effectively.

Salt Cellar Creations understands the diversity that music can express and has a professional, growing library of original works and arrangements done in simple and complex ways. Explore the offerings HERE.

SCC can also create an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you that will showcase your ensemble. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!