Conducting Styles - Which One Is Best?

First, a personal story. When I was in high school, I did an arrangement of Bridge Over Troubled Water for the high school concert band. The teacher even let me rehearse and conduct the band using his baton during class. On the night of the band concert, when it was time for me to conduct, the teacher made a simple exit as I made my way from the trumpet section to the conductor’s stand. I was startled to find that the teacher had walked off with the baton. I paused a moment. It was a large stage and to walk off to retrieve the baton would have been a big distraction. In addition, I didn’t want to embarrass the teacher by making it known that he had taken the baton.

So, I raised my hands, got the band’s attention, and conducted the piece as if it had been the way we rehearsed it. To my surprise, I discovered that I was using some of the hand nuances that I had seen my chorus teacher use. And, since many of the band members were also in chorus, none of them thought that it was odd. That night, I received a lesson in the difference between conducting with my hands and conducting with a baton. (Later, I would joke that I was a gutsy conductor, having conducted a concert band with my bare hands!)

Introduction

Music, often described as the universal language, has the remarkable ability to touch the human soul. At the heart of any musical performance is a conductor, guiding the musicians through the symphonic journey. The conductor's role is pivotal, but the tools they use can vary. In this article, we will explore the distinct styles of conducting: with a baton and with bare hands, and how these choices impact the performance and interpretation of a musical piece.

The Baton: A Precise Instrument

The word “baton” is French and simply means “stick”. It is perhaps the most iconic tool of a conductor. Its origins can be traced back to at least the 15th century.

Before the use of a proper baton as we know it today, conductors would often use a violin bow or a piece of rolled up paper since the conductor was also part of the ensemble, playing violin or harpsicord.

During the Renaissance, conductors would use a six foot long staff to keep time by pounding it on the floor to keep time. It may have been the first percussion instrument in an orchestra. A conductor had to be very careful when using such a baton, however. In the mid seventeenth century, Jean-Baptiste Lully was conducting apiece he had written for Louis XIV, using a conducting staff. Inadvertently, he stuck himself in the foot with it. Gangrene set in after that and, when he refused to have his foot amputated because he liked to dance, the gangrene spread to the rest of his body and killed him.

Later, during the 19th century, the pounding stick style was converted into the basic form that we know today. Its advantages were primarily its visibility because they were now white or ivory colored, its visual precision and its silence. The baton's length, material, and weight are carefully chosen to suit the conductor's preferences.

One of the primary advantages of using a baton is precision. It allows the conductor to make precise gestures, controlling the tempo, dynamics, and articulation of the music with utmost accuracy. The baton's pointed tip can create clear and defined cues for the musicians, ensuring that they stay synchronized and follow the conductor's directions effortlessly.

Moreover, the baton serves as a visual aid, especially in larger ensembles where the conductor needs to communicate with musicians positioned far from the podium. The length of the baton's handle gives the conductor a greater range, making it easier to convey musical nuances to the entire orchestra.

Conductors are known for wearing black, and their batons are usually white so that from a distance, the gestures being used are easy to see.

The Bare Hands: A Personal Connection

On the other hand, some conductors opt for the more tactile approach of conducting with bare hands. This style emphasizes a personal connection between the conductor, the musicians, and the music itself.

Conducting with bare hands allows for a direct physical connection to the music. The conductor's movements become an extension of their emotional interpretation, and the musicians can see and feel these emotions through the conductor's gestures. This style is often associated with a deeper level of expressiveness, allowing for more nuanced and organic interpretations of the music.

Conducting with bare hands also promotes a sense of intimacy and trust among the musicians. It encourages them to rely on their ears and their connection with the conductor, fostering a collaborative atmosphere that can lead to unique and captivating performances.

Conducting with bare hands, however, is better suited to a smaller ensemble of about 24 or less.

Contrasts and Comparisons

Now that we've explored the individual characteristics of each style, let's delve into the key differences and similarities between conducting with a baton and with bare hands:

1. Precision vs. Expression: The baton excels in precision, while bare hands emphasize emotional expression. Conductors often choose which style to use based on the size of the ensemble, the demands of the piece and their interpretative goals. For a choral piece with a very sharp rhythm, the conductor may choose to use a shorter baton to help define the rhythm. The conductor of a smaller instrumental ensemble may choose to conduct a more somber or emotional piece with bare hands.

2. Visibility: The baton provides better visibility, making it suitable for large orchestras and complex compositions. Bare hands often work well with smaller ensembles and more intimate settings, although, sometimes, larger groups, such as choral ensembles, can be conducted equally as well with bare hands, especially if the conductor wears white gloves to provide contrast against the dark clothing being worn.

3. Physicality: Bare hands require more physicality and energy from the conductor. The conductor's entire body becomes engaged, conveying their passion and connection to the music. The baton allows for more subtle movements over longer distances.

4. Communication: Both styles are forms of communication. The baton communicates through clear, calculated gestures, while bare hands communicate through the conductor's hands and body language.

5. Tradition: The baton is deeply rooted in classical music tradition, especially instrumental groups, while bare hands are often associated with choral groups, even of a larger size. Conducting without a baton is also associated with contemporary and experimental approaches to conducting.

Best Ways to Conduct

Whether using bare hands or a baton, there are some things that should always be done and some that should never be done. We’ll also take a look at a few so-called superstitions that actually have some basis to them.

Always:

> Conduct within a “box” that is as wide as your shoulders, with its bottom waist high and its top chin high. This should contain your movements 80% or 90% of the time. Poignant dynamic changes or entrances may extend beyond this box, but it should be done as little as possible to keep it a special movement. Any consistent movement outside of this box can also convey a sense of tension to the musicians.

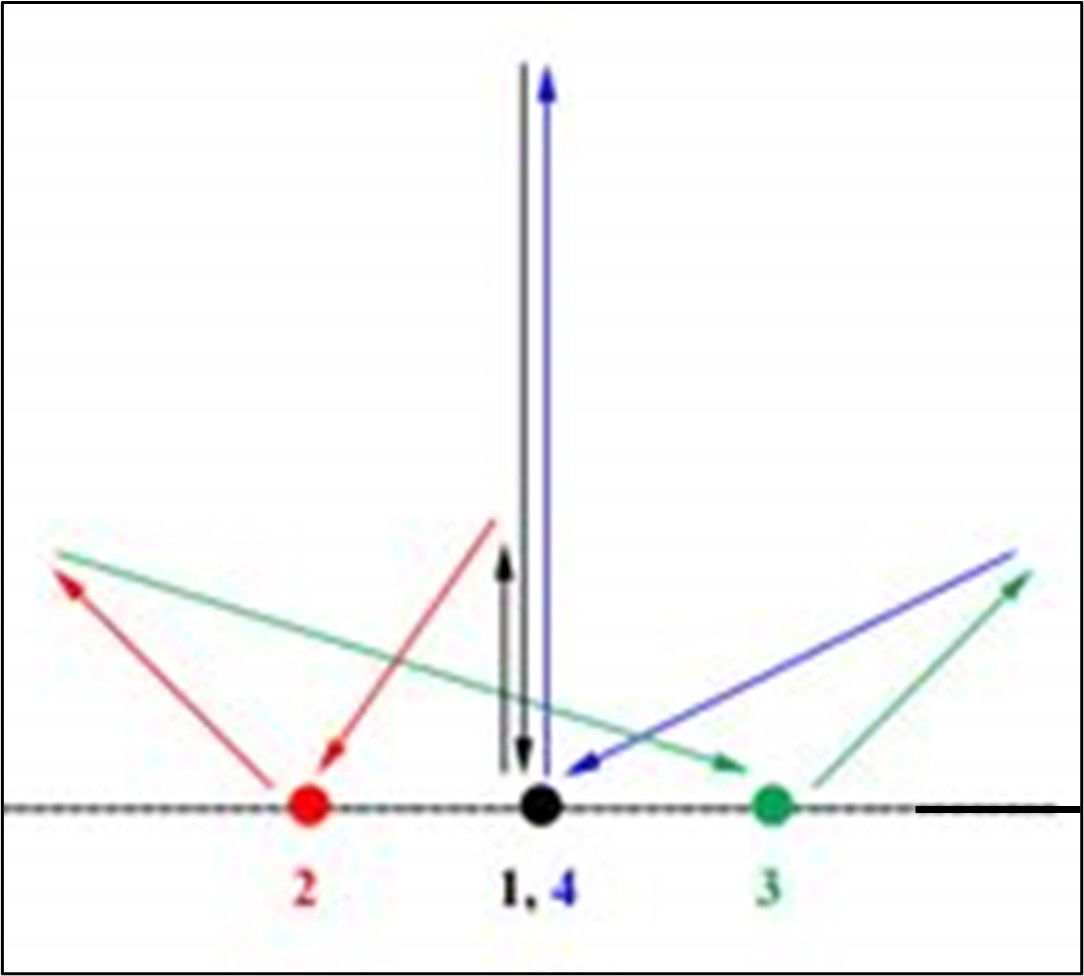

> Make your motions clear and precise. The ictus (the point in the conducting pattern that defines the downbeat) of the conducting pattern should be clear. The diagram above indicates that the ictus is always along an imaginary line, consistently about waist high. Some conductors use the upsweep of the right arm to indicate the last beat in a measure. This can be indefinite at best, since knowing where the beat truly lies is not communicated.

> The ictus (“Touch Point” of a conducting pattern) should be at the bottom of the pattern. Some conductors seem to place it at the top of the pattern, which confuses some musicians who have had proper conductors before.

> Conduct with the right hand and signal entrances and exits, dynamic changes and other specific requirements with the left. Major changes, such as an extreme crescendo or general cut off can be made with both hands, but keep the use of both hands together to an absolute minimum so that it, like conducting outside of the “box”, doesn’t lose its impact. The only exception to this is for drum majors for marching bands.

> Make the pattern at right angles to the ensemble. The reason that most conductors tend to dress in dark clothes and have white batons is so that the contrast will be greatest. This is severely minimized if the baton doesn’t move horizontally. Even when conducting bare-handed, this makes the motions most visible, even to those on stage left, where the elbow may be more visible than the hand; the motion will still be quite discernable.

Never:

> “Stab” with the baton. This is the corollary to the last one above. Only the musicians closest to the conductor will be able to tell what the motion is and the others may then perform with the wrong tempo or dynamics.

> Rely on facial expressions or mouthed commands. During a choral concert, some choral conductors, particularly in smaller groups, may indicate when to breathe by slightly raising their shoulders, raising their eyebrows, raising their heads slightly, or a combination of two or more of them. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, especially for younger singers, but those sort of things should have been refined during rehearsal and not left to being a direction during a concert.

Other choral conductors may even mouth the words to keep the singers on track. That piece shouldn’t be performed if it’s that poorly learned. There are certain times when a mouthed direction may be necessary, such as telling the timpanist, “Pick up the bass drum player”. Otherwise, there should be no mouthing of words.

So-called Superstitions

> Never point at tenors or trumpet players to cue their entrances. Make a mild indication with hand or baton and look in their general direction, but don’t make eye contact. Having been a trumpet player and a tenor, this tends to be true. The reason is a complete mystery, although the same could be said about oboe players and sopranos.

> Whenever trombone player or vocal basses do something a little “over the top”, do not encourage them. It may be something in them that not only makes them good at their music but also a little rambunctious. As before, this could also apply to percussionists or altos.

Special Conducting Situations

This section is inspired by a professor who taught where I went to college. He had assembled a pit orchestra for a live musical that the drama department presented. The orchestra pit was tiny, about six feet by 15 feet, into which were crammed an upright piano, drums kit, two trumpets, two trombones and sax, clarinet and violin. I played one of two trumpets, and the trombones sat behind us where their slides passed right by our elbows. The conductor sat on the end of the piano, conducting with his hands.

On opening night, as they fitted him with a headset used to communicate with the floor director, who was backstage, the headset refused to work. So, with only 15 minutes till curtain, the stage crew ran a rope under the stage from the control room to the orchestra pit and tied the rope to the conductor’s ankle. When they wanted music, they pulled the rope. The play ran for three nights and had eight or ten songs in it. With that arrangement, we only missed one cue, and that only by a few seconds.

He also played piano in the pep band, while conducting, also with his hands, and arms, and shoulders, and head. Sometimes, all of the technical rules go out the window and the conductor does his or her best to communicate basic things like tempo, major entrances and cut offs, and does it with whatever is available.

Conclusion

In the world of music, the choice between conducting with a baton or with bare hands is a deeply personal one for conductors. It's a decision that reflects their interpretative style, their connection to the music, and the ensemble they are leading. Neither style is inherently superior; each has its strengths and weaknesses, making them suitable for different musical contexts.

Ultimately, whether wielding a baton with precision or conducting with bare hands with heartfelt emotion, the conductor's primary goal remains the same: to breathe life into the notes on the page, connecting the musicians and the audience through the universal language of music.

Conducting is one of the things at which we excel here at Salt Cellar Creations. Our growing library of original works and arrangements have built-in conveniences for conductors, whether they conduct a concert band, choral group or string orchestra. We especially understand the challenges of music teachers, so tempo, time signature and key changes are written to allow for the most seamless transitions, while making your group sound its best. Explore the variety of exclusive music HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Austria. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!